Integration-specific MCP Servers are the wrong design

A common misconception about MCP is that first-party SaaS MCP servers (e.g. Salesforce or Snowflake’s MCP servers) are the ideal bridges for enterprises to connect to those tools. This is a fair assumption, as even OpenAI and other LLMs encourage users to connect to the MCP servers of their favorite tools. However, in practice, connecting to per-tool MCP servers is rarely the right design pattern. Instead, enterprises need custom MCP servers that mirror their specific workflow requirements.

I’m aware that this worldview seems counterintuitive. Every SaaS tool has its own successful API—why should MCP be any different? Today, my goal is to explain why MCP requires a different frame of thinking than APIs and demonstrate why an internal, unified MCP server is the better approach for a great majority of enterprises.

A Quick Analogy: Bill, Jess, and Sharon

Let’s begin with an analogy. Imagine owning an apple orchard and hiring a team: Bill, Jess, and Sharon. Bill’s job is to grow the apples. Jess’s job is to transport the apples. Sharon’s job is to sell the apples at the farmer’s market.

Despite living in separate locations, Bill, Jess, and Sharon are able to work together because you manage them. When Bill is done growing the apples, you call Jess to pick them up and give Sharon a heads up that they’re en route. The system, despite taking a fair amount of effort on your end, works.

Eventually, you grow old and need to retire. It’s time to let the business run automatically. Foolishly, you decide to hire three managers, one to manage Bill, Jess, and Sharon each. Each manager is extremely talented and learns each employee’s quirks, working styles, and needs. If you ask any manager a question **about their employee, they’ll respond superbly. In fact, each manager thinks that their employee is the most important employee in the business. However, the managers don’t talk to each other and instead rely on you to coordinate things. Ultimately, you’re back to square one: you’re still stuck managing three people!

While slightly reductive, this is how first-party MCP servers work. They don’t actually help businesses solve big problems, just automate little actions. To better understand this, let’s differentiate the purpose of MCP and an API specification.

MCP is not an API

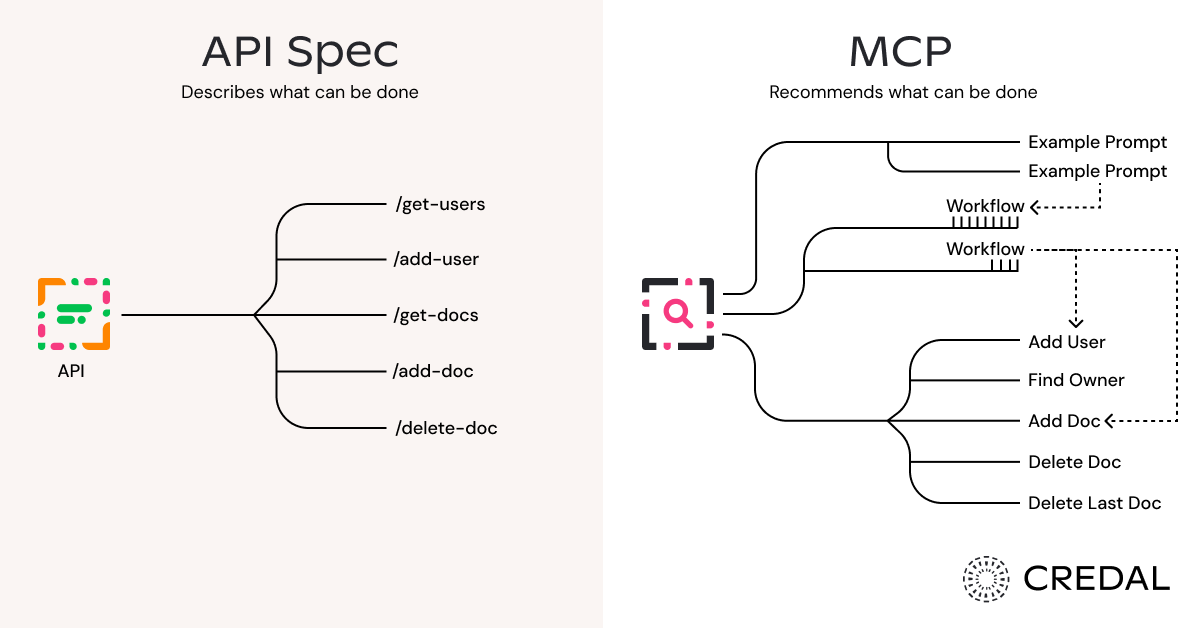

Let’s explore the distinction between MCP and OpenAPI (a common API specification standard). Colloquially, MCP is often treated as the OpenAPI equivalent for AI agents; it’s an apt analogy from the perspective of what connects to what. However, MCP and OpenAPI aren’t exact corollaries; instead, MCP is more like a hybrid of OpenAPI specs, tutorials, and code sandboxes.

OpenAPI is just a descriptive standard. It demarcates what an API does, detailing the expected inputs and outputs. The rest is up to the human. With APIs, a human developer has traditionally been in control of exactly how that API is used. A human chooses how to call it, why to call it, and what to do with the response. For example, an engineer with Salesforce access knows exactly what’s in their Salesforce account and how it should be integrated with an internal system. The human determines what the integration should do and then after relies on the OpenAPI standard for implementation.

However, AI Agents, in a vacuum, don’t immediately know what to use an API for. The purpose of an MCP server is to help them with that task. MCP accomplishes that by providing common prompts, data workflows, and goals of a hypothetical integration. Unlike OpenAPI, MCP is a prescriptive standard—it doesn’t just describe how a connection works, but also establishes how it could be used. Granted, so does well-written API documentation (e.g. think Stripe’s illustrious docs), but MCP actually codifies a prescriptive approach.

However, if the goal of MCP is to provide context to an AI agent, then that misaligns with disconnected, first-party SaaS MCP servers. An MCP server from Hubspot, Salesforce, or Snowflake can only provide context of how their tools work in a vacuum. That, after all, is the only information that the engineers at Hubspot, Salesforce, or Snowflake know. They’re not familiar with how a specific enterprise is using their tools, and even if they were, that shouldn’t impact a universal MCP server intended for all of their customers.

Additionally, first-party MCP SaaS servers face an idealism problem, where each MCP server is designed around the product’s ideal customer profile, not their median user. For example, in the eyes of Hubspot, a customer is idealistically using the platform as a unified CRM, marketing automation platform, billing system, data hub, et cetera. But in practice, that’s rarely the case! Enterprises use multiple, overlapping tools for various tasks, syncing data from system to system. For example, many Hubspot users treat the platform as strictly a marketing hub that integrates with their Salesforce and outreach tooling.

Let’s use an example to demonstrate this from the client’s point-of-view. Imagine an AI agent that interfaces with both Salesforce and Zendesk’s MCP servers. Both servers will have a tool description along the lines of “use this to create a support ticket.” To an AI agent, the difference is unclear; however, to an employee, it’s obvious that Salesforce tickets are for sales and US customer support while Zendesk is for international support. However, the individual MCP servers have no way to demarcate that; they’re written universally for all Salesforce and Zendesk customers, not any specific organization in question.

Instead, enterprises need to build their own internal MCP server.

The risk perspective

Another way of thinking about first-party SaaS MCP servers versus an internal MCP service is from the standpoint of risk. Enterprises generally don’t like the idea of AI having open access to systems as that might create arbitrary paths. And, anything with access to internal data, including email and communications data, is an extremely open sandbox!

This presents a security risk—imagine an AI Agent that writes code to leverage the Snowflake API, but accidentally installs malware with access to production data. The goal of MCP should be to eliminate arbitrariness, not introduce it; this is controlled by trusting an internal MCP server with the appropriate guardrails for transacting with the underlying APIs.

The freedom of an internal MCP server

With an internal MCP server, enterprises can personalize and organize the underlying integrations to their tooling, leveraging traditional APIs. An internal MCP server can expose tools to AI agents that are mapped to existing workflows, not individual platforms.

For example, take the aforementioned Salesforce and Hubspot example. Instead of exposing discrete Salesforce and Hubspot MCP servers, a unified internal MCP server could have a single tool for creating a new sales prospect. When invoked, this create_customer_record tool automatically creates a record in Salesforce and reconciles it against a marketing profile in Hubspot. Now, the AI agent is working with an existing workflow, not trying to re-invent it.

This might appear regressive; after all, it relegates some “intelligence” away from AI agents and back to humans, as humans have to design the MCP server’s internals. However, this is necessary if enterprises want AI agents to abide by a system that their own human employees originally strung together.

Additionally, a unified MCP server is easily scalable. Let’s extend the sales administrative example. The create_customer_record tool might not just (i) insert customer data in Salesforce and (ii) modify a field in Hubspot to disable advertisements, but also (iii) insert a log into Snowflake for future analysis, (iv) fire off a job in Clay for marketing automations, and (v) blocklist a record from Apollo to prevent duplicate outreach—all while also adjusting an “Active Leads” table in Google Sheets. If you work at an enterprise, this piecemeal workflow might sound familiar.

The value of an internal MCP server isn’t just practical. It’s theoretically superior

This crusade against first-party MCPs might sound like a story of practicality over theory. But first-party MCP servers also misalign with the purpose of SaaS tools. Companies don’t purchase SaaS tools to solve a siloed problem. Instead, they purchase SaaS tools to work towards a collective problem. For example, even if used to the maximum, Anaplan cannot alone exist as a financial planning tool. It needs data from Quickbooks, bank statements, and Excel sheets to actually provide insights.

Another way of thinking about it is that entire departments at an enterprise might operate like a well-oiled vehicle. Meanwhile, SaaS tools are like car components. Some might be a critical one (e.g. the engine or chassis) or a small one (e.g. the steering wheel). Regardless of the size, no manufacturer of a single component would possess documentation on the other parts.

A closing thought: is there any use to first-party MCPs?

This begs the question for why first-party providers are building MCP servers. Candidly, there is an element to hype involved; MCP launched to a lot of fanfare, and first-party MCP server releases quickly dominated headlines.

That said, first-party MCP servers are fantastic for consumer applications. For instance, imagine a digital assistant application that connects to Expedia’s MCP server to book flights. In this scenario, the request is isolated—it doesn’t need to sync with other applications.

Yet, for most B2B SaaS software, this independence is rare. A vast majority of businesses purchase tools for their strengths and rig them together through human hands, Zapier-like integrations, or code. Accordingly, an internal MCP server is the way to go.